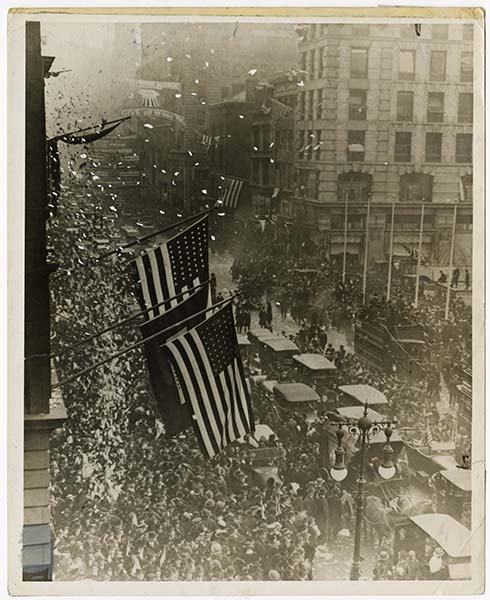

This Veteran’s Day marked the one hundred year anniversary of the armistice signed between Allied and Central Powers of World War I at Compiègne, France to end fighting on the Western front. The conflict resulted in an unprecedented level of death and destruction as the products of industrialization–airplanes, tanks, submarines, machine guns, and poison gas–were deployed as modern machines of war. Alongside these new technologies photography played a more central role than ever before in documenting the war. The Photography Collections at UMBC include a large group of photographs from World War I that were distributed as press images by the news bureau Underwood and Underwood. Documenting every aspect of the conflict, from training drills to life in the trenches, from explosions on the front to the burial of fallen soldiers, this archive provides valuable historical evidence, and demonstrates how photography brought the realities of the battlefield into people’s homes.

Whereas photography had been present at conflicts during the nineteenth century, including the Mexican-American War, Crimean War, U. S. Civil War, and Paris Commune, slow exposure times and cumbersome equipment meant that the action of battle evaded capture by the camera. Instead, portraits of soldiers and views of the aftermath of battlefields stood in for the events of combat. Due to the high cost of photographic printing, the images that circulated in newspapers and magazines hewed to traditional methods of illustration, and artists translated photographs into woodcuts or lithographs that could be more easily reproduced. With the development of halftone printing in 1881 and later advancements in film speed and more portable cameras, the action of battle was captured in photographs for the first time during World War I and distributed quickly on a global scale through news agencies and the press.

Soldiers carried small and easy-to-use Kodak brownie and vest pocket cameras with them to the front, sending home pictures that documented an individual experience of the war. Meanwhile, armies employed staff photographers who provided documentation for military use. For example, the American photographer Edward Steichen served as chief of the Photographic Section of the American Expeditionary Forces and produced aerial photographs of the Western Front from a birds’ eye view. His photographs served as reconnaissance for strategic positioning and tracked German movements. Most nations did not allow press photographers embedded on the battlefield, so the photographs disseminated through news media came directly from the military. Many of the photographs distributed by Underwood and Underwood bear stamps indicating the date that they passed review by government censors. Published images were also accompanied by explanatory captions, which can also be found on the verso of many of the photographs in UMBC’s collection. The information received by readers back home was thus shaped by the military’s official point of view along with that of the news source.

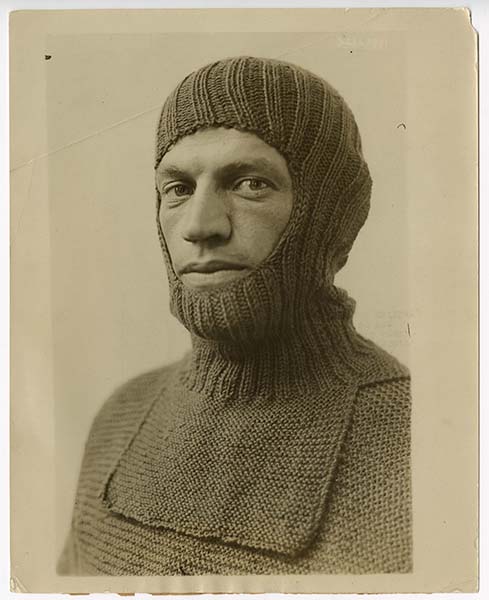

The World War I photographs in UMBC’s Special Collections encompass a wide variety of subjects, including scenes from the trenches and more light-hearted moments of camaraderie among troops. While many of the images are visually striking, their ability to convey clear information about the events of the war often rests on the text that accompanies them. It can be difficult to tell the difference, for example, between a training maneuver and the heat of battle. What do we make of a portrait of a man wearing a strange knitted balaclava or a glamorous woman in nurse’s uniform holding up a sash covered in military insignia? In the case of the former, the caption informs us that this man is a sailor wearing woolens knitted by women volunteers from throughout the United States, who supplied their own yarn and their time to the war effort. In the latter image, Detroit society girl and New York concert singer Marjorie Kay displays the 154 decorations that she collected while serving as a nurse in the U. S. Army Ambulance Corps. The stories told by these photographs—and about the “war to end all wars”—are manifold.

-- Beth Saunders, Curator and Head of Special Collections & Library Gallery

To view these World War I photographs and others from the Underwood and Underwood archive in person, stop by the Special Collections Reading Room in the Albin O. Kuhn Library, open Monday to Friday 1:00-4:00pm and Thursday 1:00-8:00pm.